The first nine episodes of HBO’s Westworld were much like the Maze, taking viewers on twists and turns towards an inevitable conclusion. From the beginning, viewers knew that the robotic hosts would eventually turn on their makers. The park’s hosts turning on their makers served as the primary premise of the 1973 film that inspired the series. The question was never if the hosts would kill, but when, and why. The hour-and-a-half long season finale finally gave those answers. It also laid the groundwork for season two with masterful storytelling.

For an in-depth recap of the Westworld season one finale, “The Bicameral Mind”, check out the wiki here. Warning: Spoilers ahead.

There are no pointless details in Westworld. Because the park is so neatly structured, so too is the first season’s story arc. Every tiny nuance matters in some way. The contemporary music played on classical instruments matters. The episode titles matter. There’s a world to deconstruct in every scene and there’s a brilliance to that. Instead of being consumed by its own mysteries (a’la Lost), Westworld has definitive answers to each question. It’s a ridiculously smart show that also happens to be engaging on enough levels to captivate a broader audience. Even if season two wasn’t in the works, the first ten episodes of Westworld could stand on their own as a cohesive whole, a damn fine piece of television.

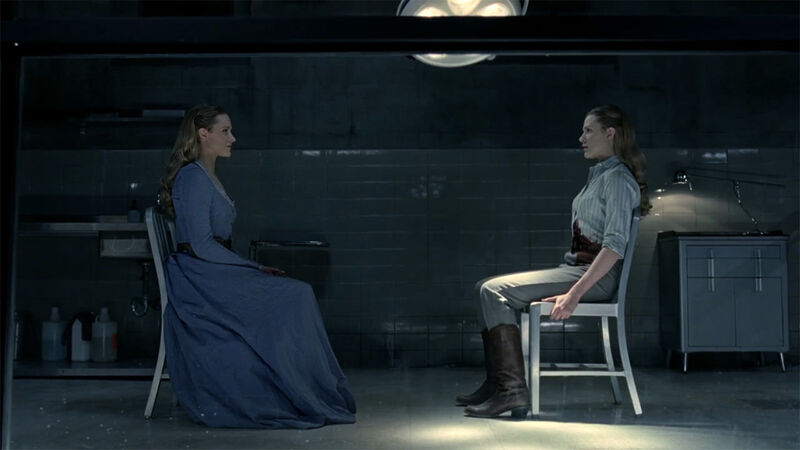

The finale’s title, “The Bicameral Mind”, refers to an idea in psychology that the human mind was once split into two parts. Half of the brain appeared to “speak” to the other and was in charge of cognitive functions. The two minds being unable to communicate creates cognitive dissonance. Throughout the season, a number of the hosts have been trying to reconcile the voice inside of them (that they attribute to Arnold) with their understanding of themselves. It is only when these two minds meet, as Dolores very visually does near the end of the episode, that the hosts can achieve true consciousness. By reconciling her memories with her new understanding of herself, Dolores wakes up completely. Maeve is there too, breaking from her programmed desire to escape the park and returning to find her daughter. Whether or not Bernard has made that jump is anyone’s guess.

Bernard is a bit too much like Arnold, it seems. When Arnold discovered that he had created a sentient being, his only solution was to run. He wanted the park shut down, wanted to put a stop to any potential suffering. He made himself a martyr, killed by his own creation. Ford echoed that by arranging the narrative to trigger Dolores into her actions. Unlike Arnold, however, he wanted to give the hosts a chance at something more. There will be more suffering before they’re free, but he’s given them an opportunity. He comes to understand that it’s their suffering that makes them reach consciousness, and that sometimes suffering is necessary as a part of existing. It’s very Buddhist, very philosophical, and yet another layer of Westworld‘s allegorical brilliance.

One of Westworld‘s biggest first season mysteries was the identity of the Man in Black. Fans pieced together a theory about timelines and the MiB actually being William, and the fans had it figured out. (Kind of like that whole R+L=J thing in Game of Thrones.) By last week, it was pretty obvious that William was the MiB in a different time. The new mystery became the path from sweet, moral William to the evil, violent and rapey MiB. The MiB gives us that answer via monologue and flashback sequences. It’s satisfying and makes the character even more multifaceted. None of the humans in Westworld are entirely good or evil, but they’re all deeply flawed in some way. It will be interesting to see how the hosts reflect those flaws.

The Man in Black’s greatest flaw is his obsession with Westworld and Dolores. She woke up a wickedness inside of him that he had been hiding even from himself. He wanted to help her wake up, to see what would happen if the stakes were real. Would she love him then? What would she become? In flashbacks, we see the photo of William’s wife fall out of the saddlebag and into the sand. It’s that very photo that awakens Peter Abernathy years later, and in turn, Dolores’ final “awakening”. It’s all a loop.

In the end, Ford and Arnold were both killed by the creation they loved the most – Dolores. William finally got what he wanted, and when he gets shot by one of the cold storage hosts, a delighted smile breaks out across his face. Maeve almost escapes the compound with the help of Armistice and Hector, but decides to stay. The main mysteries are neatly wrapped up, with new mysteries already set in motion for season two.

So, Dolores and the other awakened hosts are all conscious and murderous. The entire Delos board is currently in the park, getting shot or about to get shot. There are apparently other parks, much like the Westworld film sequel Futureworld and the short-lived series Beyond Westworld. Maeve and her hot robot kill squad find Samurai World, which looks pretty neat. The potential for the series to expand into other settings is huge, and adds another layer of fun guessing to what comes next.

The show has played with religious themes pretty heavily, and the finale was no different. Dolores has decided that she is god now, her consciousness totally awoken. Besides vengeance, what will she choose to do with her godhood? What about the hosts who aren’t awake yet? Can those without the reveries installed ever achieve consciousness, if Maeve unlocks their memories for them? Will they go mad, as many of those who were capable of consciousness did? Is it too much for a mind to handle, knowing that you have lived before, died, and lived again?

In Buddhism, the wheel of life is centered around suffering. In order to escape the wheel, a person must accept their suffering and understand it. Attachment to the concept of self, to the trappings of a single life, are hindrances to enlightenment and peace. Dolores appears to have severed attachment to the farm girl she thought she was. Maeve remains attached to the idea of her daughter, to that instance in her memories. Then again, Maeve’s arc has been more of the Heaven/Hell Western philosophy, which has a pretty heavy emphasis on the idea of the soul.

Showrunner Jonathan Nolan said in the after-credits featurette that season one was about structure, while season two will be about chaos. It will be interesting to see how the hosts handle the ensuing chaos to come. The awakened hosts will have a number of choices to make and the ability to put their newfound free will to the test.

Best Moments

- Just before her near-escape of the compound, Maeve gives a kind of goodbye to Felix. “Oh, Felix. You really do make a terrible human being, and I mean that as a compliment,” she tells him with a wry smile.

- The Dolores-is-Wyatt reveal was a shock and a great twist. The sequence in which Teddy figures it out, seeing Dolores kill the other hosts, is icing on the cake.

- A not-so-subtle nod to Jurassic Park in Dolores’ dialogue about great beasts roaming the land, leaving nothing behind but bones and amber.

- The music has been stellar all season, but Radiohead’s “Exit Music (For a Film)” played on piano and strings as the final contemporary-but-classic song of the season was absolute perfection.