Since getting his break as a sound designer on Destroy All Humans! 2 in 2006, Mick Gordon has worked on some of gaming’s most interesting soundtracks. He’s the man who scored the moody atmospherics of Wolfenstein: The New Order and Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus; seasons one and two of Killer Instinct; and most recently the brilliant DOOM reboot, where he succeeded in capturing the horror and insanity of a Martian hellscape.

With that soundtrack recently having been given a physical release, what better time to catch-up with the 32-year-old Australian about his career and influences…

Mick, let’s start with a bit of background as to how you got into writing soundtracks for videogames…

“Okay, so, all I did at school was play videogames. I wasn’t very good at math, or at English or Science, so when I got to being eighteen, I suddenly started to worry that I didn’t have any skills other than being pretty good on guitar. I also played a lot of videogames, but again, I wasn’t sure how that could help me carve out a career. At the same time this was going on, there was a culture shift in how music could be recorded.

You didn’t have to retreat into the hills and spend three months at a recording studio anymore. You could do it on a laptop. I basically taught myself how to do that. After awhile, I burned the stuff I’d made onto a CD and started sending them out to different game developers, and to my shock I started getting callbacks from people saying they liked my stuff. That was the beginning of it all…”

Why game soundtracks and not, say, film?

“Well, this was the PlayStation One era, and although I loved games, they were still this geeky thing really. I didn’t foresee the explosion that happened with games, them becoming a billion billion billion dollar industry, but that happened, and therefore it chartered the direction I went off in.

It was totally a case of right place, right time – getting in on the ground level. And I always felt I understood videogames, whereas with film, I just never felt suited to it. I never felt a calling for film like I did with games, I felt like I’d be pretending at it, really…”

The DOOM soundtrack is heavy metal on the highest setting. As a guitar player, it must have been hell – in a good way, obviously – to work on, no?

“It’s funny, because when I started making music for games, guitars were out. They were in pop culture as a whole, and as a guitarist it felt like the rug had been pulled out from underneath me. I managed to get them in my work more and more over time, but even when I started on DOOM, there was real resistance to guitars, because the thinking was that they were very eighties and they felt it dated the game.

But I knew DOOM needed them so I started sneaking them in. Then I started sneaking more in. And the more I did, the more it felt like DOOM…”

I’ve read quite a lot about the ‘DOOM instrument’ you used in composing the soundtrack. Can you explain that a bit more?

“Well, you know I was talking about the shift in how people recorded music, from studios to laptops? Well, that’s great… to an extent. The computer just isn’t a replacement for everything. The problem with it is that anything the laptop can do well, you end up gravitating towards that, and anything it struggles with, you put aside, so it kind of influences how you write.

And if you’re using the same synth plug-ins as everything else, there’s a danger that you’re going to sound like everyone else. The DOOM team were really keen on new sounds, hence the resistance at the beginning to guitars, and we kind of stumbled upon this idea of taking the raw building blocks of any sound – noise and sine waves, consonants and vowels essentially – and playing them through circuitry.

It’s not like treating the circuitry, you’re actually trying to capture the essence of the circuitry. Then if you do that with fifty different things, it’s like they become their own band. It’s like the machines start doing things on their own rather than you sitting down and using the machine.”

Can you explain a little about how you work to a brief on a game like DOOM, or is it more collaborative than that?

“So there are two things I try to do, and the first of those is try to extract the intuition the team has. They’re the experts in the game, not you, and I’m there to extract their intuition. I hang out in their offices and sit in the meetings and look at all the artwork – just to soak everything up. That way, when I’m back in my studio making decisions about how much distortion to put on something or what the tempo should be or whatever, then that intuition can inform what decisions I make.

I also always try to put myself in the shoes of the player. What I normally do is ask the studio to send me a video of someone playing through the level, and I’ll throw that up on a TV and I’ll put a controller in my hand, and just try to imagine what, as a player, I should be listening to at any particular point.

Should it be fast, should it be sad, should it be heavy. What are the emotions? I’ll make notes and I have a little tap tempo app on my phone I’ll mess around with rhythms on, and that’s kind of how the whole process begins really…”

I know the chainsaw effect from the original game made it into the reboot’s soundtrack, but what other influence did you take from DOOM’s history?

“Well, in id’s office, they have this enormous glass cabinet containing all of DOOM’s history really. The are these sculptures that the team made of the demons from the 1993 game, that they made just to take photos of, that then became the animations in the original game. There’s a model of Spider Mastermind in there, and photos of it spinning around, and that is really cool. I was in their office recently and I was lucky enough to meet Kevin Cloud, one of the original guys, and his arm, his hairy right arm, is Doomguy’s arm!

They’ve got all the original sound effects too, obviously, but I find the trick of using that stuff, is to try to remember the feeling you got from hearing that for the first time, then trying to replicate that, rather than just replicating the sound.”

Okay, I’m going to chance my arm here. DOOM Eternal just got announced at E3. What can you tell me about the music you’ve worked on for that?

“So I haven’t been instructed on what I can say and what I can’t say yet, so I’m going to play it safe and not say anything! However… I think I can probably say that the music is going to be in the same universe. I always feel really disappointed when I play a game and I think the music is great, and then by the time the second one comes around, the music is completely different and it loses the feel of what you liked about the game in the first place.

We spent so much time defining the sound of DOOM, we’re not going to abandon it now.”

Awesome. Finally, you spend a lot of time making music on computers. Do you ever yearn to make music with real people?

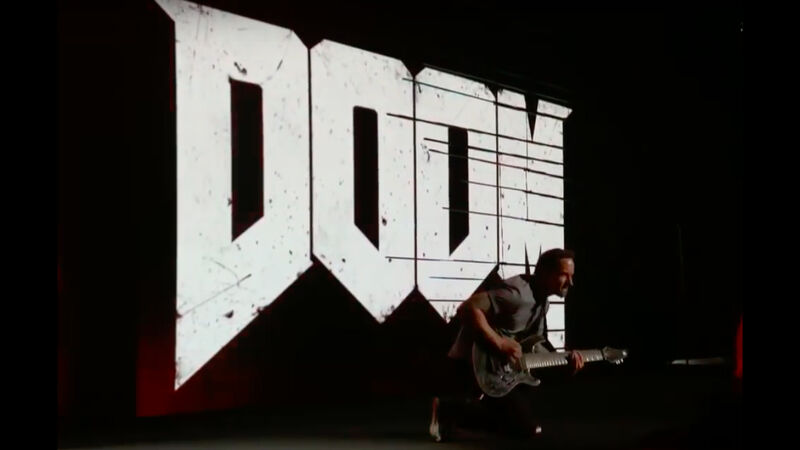

“I do, but these days I’m so slammed with game work, I never can find the time to do that. I’ve had some opportunities to play the DOOM soundtrack live in front of a few audiences. The goal for next year is to get a band out on the road to do a few dates around the world of us playing videogame music.

It’s been done before with an orchestra, and I’ve loved those shows, but I don’t think those shows really capture the excitement of games, and so that’s something I really want to do.”

The DOOM soundtrack is out now via Laced Records, and comes in four formats: a Deluxe Double CD, a Double Vinyl, a Special Edition Four-Disc Vinyl and a Special Limited Edition Vinyl Box Set.

For more information on the DOOM composer and his work elsewhere, head to www.mick-gordon.com.